"SPILT INK" & Genealogy - DNA Forum

| Forum: Spilt Ink | |||||

|

|||||

|

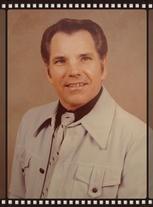

A. J. Smith

Posts: 29 View Profile |

The Heritage of A.J. Smith Posted Friday, September 22, 2017 03:37 PM The Heritage of Alva Smith, Jr. © 2017 My mother was the daughter of a Northeast Arkansas cotton share cropper. He was a Pentecostal preacher on Sundays. Mom’s mother hailed from Illinois, but died at age twenty-two in the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918, when Mom was three years old. Northeast Arkansas was hard hit by that plague. Logging companies were clear-cutting the ancient hard-wood forests, operating from barges located on the Black and the White Rivers. One barge might hold a sawmill, another a barracks where the loggers slept and another a kitchen and dining hall. Water for the kitchens was taken from the rivers and sewage dumped back into the same streams. My family lost several members that year, who are buried in the Nelson Cemetery near Datto, Mom’s birthplace. My grandfather’s brother, Harva (pronounced “Harvey”) Larkins lies next to his wife. They died within hours of each other. Their graves are marked by their names etched into a piece of scrap metal, the letters made by Ira Larkins, their son, with holes punched through the metal using a nail. Ira, called “Sonny,” survived as did my grandfather, James B. Larkins and my mother Lura Mae Larkins. My grandmother, Laura Nelson Larkins, who died the same week, lies nearby. At about age seven, Mom was sold into slavery. Well, slavery might be an exaggeration. She worked for a family as a household servant until she was in her early teens. She was paid one dollar per week. On Saturday, she was given a dollar bill, an envelope, a sheet of paper and a stamp. As a part of her education, she would write a letter to her father, fold the dollar bill inside it and mail it to him. Another parent might think he would have saved it for her, but that was not the case. The man who raised me (I'll call him “Dad.”) was the oldest of nine children parented by two mixed-blood Cherokees, whose surname was “Smith.” The Smith grandparents' farm in North Carolina seemed to be the main reason they were judged to be Cherokee rather than Americans under the Indian Removal Act. Their farm was taken. They were sent to Indian Territory, along the Trail of Tears, in 1838. My Dad, from my earliest years, told me we were Cherokee. He died when I was twenty-six and living in New Mexico, working on the Navajo reservation. While I was in Tulsa for his funeral, Dad's younger brother, John, also called “Blind Bear,” conferred his job upon me (Family Historian) and told me about the family's early history. He decided my Indian name should be “Stands Firm with Pony.” He pointed out that the name was Lakota, not Cherokee, but added, “You have the Spirit of the Lakota in you. When he was about three, Uncle John found a dynamite blasting cap, laid it on a stump and hit it with a hammer. His eyes were destroyed; hence his Cherokee name. For that reason, he was the only child in the family who went to school, “The Arkansas School for the Blind.” My ancestors were in the contingent who fought blizzard conditions in southern Missouri but escaped the Blue Coats, wintered in a cave near Yelleville, Arkansas, and swore only grandma had Indian blood. Eventually, somehow, they came to own the eighty-acre farm around the cave. They built a two-room log cabin, which still exists, but has been taken apart, moved to near the mouth of a cave, and reassembled. In its original location is a modern home. An attempt was made (I don't know by whom.) some years ago to make the cave into a tourist magnet called “Cherokee Cave.” It was unsuccessful in no small part due to its remote location, though its unspectacular interior didn't help. After the turn of the Twentieth Century, the Smith family moved to the Tulsa area. Dad, the eldest child, was eleven at the time. Grandpa and Dad worked as mule skinners in the Glenpool oil fields. Later, the males of the family traveled, following drilling operations. I have a photograph of Dad and two unknown men on the day the gusher was brought in on the State Capitol Grounds in Oklahoma City. Dad was twenty-six years older than Mom. Prior to their having met in the early 1930s, Mom told me, Dad worked on the “Hunnerd'n'One” ranch, first as a cowhand, then as a roustabout on drilling rigs. I have found no way to verify that. Dad never spoke of it, except in general, talking about his experience drilling oil wells. In 1934, Mom and Dad were back in Tulsa. My sister was born on the last day of that year at Morning Side Hospital, now Hillcrest Medical Center. About 1937 they moved to Lyons, Kansas, where an extensive drilling operation was going on. Dad couldn't hold his liquor. He would get slobbering, staggering drunk after drinking two beers. One payday he and a friend (who had a car) got drunk and stayed that way all the way to Illinois where his friend tried to out-run a train to a crossing. The race ended in a tie. Dad was hospitalized in a coma; his friend was killed outright. Dad got fired in absentia for not showing up at work. Mom and Sis had been living in a tiny camper trailer (I have a picture of them sitting on the steps.) which belonged to the drilling company. Dad's boss, and my sperm donor, John (or James) Olin Miller, (called by his initials, J.O.) had to evict them but invited Mom and Sis to stay in his quarters. Since Dad’s whereabouts was unknown, they had nowhere else to go, had not eaten for a few days, and dinner was included, Mom accepted J.O.'s invitation. According to Mom’s confession on what she thought was her death bed, J.O. was from South Dakota, a Lakota Indian. (Did Uncle Blind Bear know that? Your guess is as good as mine.) It was surprising to me that Mom even knew the word “Lakota.” Natives (both bloods and breeds) from all over the Great Plains, caught up in the Great Depression, desperately took the low paying hazardous jobs offered in the oil fields. Dad was back in Lyons sometime after my birth, December 5,1939, with a new and ugly scar across his nose. (When asked, he always said, “A train ran over my nose.”) I'm not sure of the sequence of events but I understand J.O.'s wife visited from South Dakota and took exception to his live-in guests. The Smith family somehow found their way back to Tulsa County. Dad landed a job managing The Old Moon Gasoline Plant in the Glenpool basin, specifically “Liberty School District,” and remained there throughout World War II. A benefit was that a house existed on the lease. The family could live in the house and run livestock on the property. There were also a lot of cotton tails and squirrels there. For the first seven years of my life, I listened to cows mooing in the night along with the kerflume! kerflume! of the pumps. We ate a lot of chicken-fried rodents. Mom worked at Douglas Aircraft Company, making A-26 bombers, as “Rosie the Riveter” during World War II, carpooling her commute. The oil wells produced a by-product called “drip gas” which worked in cars, so rationing was not a real inconvenience. Since rabbits and squirrels were free and not rationed, we ate regularly. Dad was a good shot. I still have his Remington Speedmaster 241 .22 Short. When I was at Will Rogers, Billy Chambers and I discovered the old lease, obtained permission, and hunted on the property. We brought home a bunch of bunnies. There was a boy, about my age (4-5), who lived on a farm not far from us. We played together. One day, his parents asked my folks if I could go to prayer meeting with the family on Wednesday. My parents gave their permission, Dad with some reluctance. I enjoyed the singing and things went well until the Preacher began his sermon. Soon the audience was moaning and screaming “Amen! Praise the Lord!” Some fell out of their pews. They began writhing and rolling on the floor. Some were slobbering, their eyes showing white, talking in tongues. The screaming got louder. I had no idea what was going on. I started to get frightened. The Preacher left the pulpit and began stalking up and down the aisles, screaming his sermon. He would pause, face a person on the end of the pew, shake his finger in their faces and scream, “You have sinned, Brother! You have sinned, Sister!” He seemed to pay no attention to those rolling on the floor. I was sitting next to the aisle at the end of the pew. When he arrived at me, he shook his finger in my face and screamed, “You’ve sinned, Child!” I burst into tears, left my seat and ran up the aisle and out the front door. Outside, I had no idea where to go so I stood at the top of the stairs. After a while, I moved to one side, sat down on the top step, and cried, not sure what was going to happen to me. No adult followed me from the church. I sat there in mortal fear. Eventually, when the service was over, the Preacher stood at the door and shook hands with the departing parishioners. I tried to shrink into the night, hoping nobody would notice me and kill me for what I’d done. Eventually, the family who had taken me to church came out. The mother grabbed one hand and the father the other. Their grips were painful. They jerked me to my feet. “Oh,” said the mother, “God is so mad at you! You defiled his house!” I didn’t say a word. They dropped me off in front of my house. I ran inside and cried inconsolably. My parents held me in their arms and calmed me. I was finally able to tell them what had happened. “Is God gonna kill me?” I asked. “No, Son. God is kind and gentle,” said my dad. “But I may kill that son of a bitch who took you to that so-called church.” He left the house and I heard his old pick-up truck start, then the wheels grinding gravel as he drove away. He wasn’t gone long. When he got back, my mom bandaged the bleeding knuckles on his right hand. Dad hadn’t killed the fellow, but my guess is that he gave him some bruises to explain. We never talked about what had happened but I didn’t play with the little boy any more. For years following that incident, I had the same recurring dream. I was sitting in the bleachers at Liberty Consolidated School, much as if I had been at one of my older sister’s basketball games when the same preacher would begin to stalk the aisles, ranting and screaming. Then he would say, “Brother Jones will pray while I kill!” He made his way down the row of people, using a butcher knife like the one my mother used in the kitchen, cutting people’s throats the same way my dad slaughtered a calf. When he got to the person sitting next to me, I woke up crying. I didn’t go to church again until I was in Junior High School. Sheridan Avenue Christian Church was a lot more peaceful. After the War, during the Planting Moon, we moved to the ancestral log cabin (described above) near Yelleville, Arkansas. Dad hoped to live a hunter/farmer life. My parents went to Arkansas flush with savings from the war years but it disappeared quickly when they bought livestock for the farm. Dad's return to Native American values didn't go well. The forests had been hunted out. A drought, followed by too much rain, killed the crops. A forest fire, a freeze during the mid-winter Moon, and probably starvation, finished off the animals, including the coon hounds. Mom was accused by the Forest Ranger of starting the fire, but she sold him a hog and he didn't press the investigation. I'll never forget Mrs. Ledbetter, my second-grade teacher. There was no free lunch for hungry kids at Yelleville Consolidated School. Mom often fixed a lunch for me, a biscuit and bacon sandwich, but often we didn’t even have that. If a kid's cafeteria account was emptied one day, he didn't eat the next. One morning, Mrs. Ledbetter read aloud a list of the kids whose lunch accounts were overdrawn. I was one, of course. She questioned each child who was listed, about half the class. Nobody in Yelleville was well-to-do. All the kids promised (under duress) that they would bring money the next day. Few did. Mrs. Ledbetter lined up the freeloaders and led them to the front of other classes, where she announced, “These children are liars. They promised to bring lunch money today.” I've never felt guilty about entertaining the fantasy of Mrs. Ledbetter starving in her old age. It’s not surprising that I turned out to be a bleeding-heart liberal who thinks all children should have a free breakfast and lunch in the school cafeteria, funded by taxing the wealthy. Or, even better, by taxing people like Mrs. Ledbetter. The family made plans to abandon the farm and return to Oklahoma in the Spring. It was a hard winter, with lots of snow. Still today, the country song, “If We Make It Through December,” reminds me of the winter our family spent in Arkansas. Dad hitchhiked back to Tulsa to find work and Mom found a job in a khaki uniform factory in Harrison. One evening the car pool vehicle broke down in a snow storm. Mom walked to our house. The last hundred yards, she crawled through the snow. Sis and I were there with fires in the fireplace and the kitchen wood-burning stove when we heard her tapping on the door. We brought her inside and warmed her. Fairly soon, Dad had a place to live and was working. Mom amassed enough money to buy bus tickets to Tulsa. The family spent the next several years moving between apartments, just ahead of angry landlords. My parents did what they could to feed us. Dad worked for fifty cents an hour at Empire Pattern and Foundry, making small pieces of scrap steel out of big ones so they would fit into the smelting pots. I have his Withholding Tax Statement from 1956. He earned $750.01 that year. Mom waited tables in a restaurant on Pine Street and brought home leftovers. “Leftovers” were the food people left on their plates. Sis and I looked forward to Mom’s return every day she worked, which was most days. When I was about ten, Dad came down with a bad case of the Flu. He never fully recovered his health, although he lived another fifteen years. About that time, my still fairly-young mother discovered a love for dancing and was often out in the evenings, usually at Cain’s Ballroom, with my teenage sister. In addition to her confession about my parentage, on my mother's (not quite) death bed, she told me the following story. She had been dancing at Cains and decided to stop by her partner's place to say goodnight. Then she went home and crawled into bed with my amorous Dad. The result, she claimed, was fraternal twins, one fathered by her dance partner and the other by Dad. The twins don't look very much alike but do favor their individual suspected daddies, so who knows? To her surprise, Mom recovered, wished she’d never told me and swore me to secrecy. I've never shared this with my brothers. My parents were divorced soon after, much to Dad’s chagrin. As he had loved me, he loved the twins as his own. He was never far away for the rest of his life. 1950's morals were not prepared for my family. Straightening out the twins' surnames, was an issue. It was first decided it would be Smith because Mom and Dad were still married when they were born. That required a court order changing their names after my parents' divorce. Mom's dance partner was somehow credited with fatherhood of both, and birth certificates were changed. Mom married her dance partner, a WW II Navy veteran. When I was twelve, they bought one of the houses that was being built for returning veterans, near the Admiral Twin Drive-In theater in the Val Charles subdivision. For the first time in my mother's impoverished life, she was a home-owner and would not have been prouder had it been a mansion. Step-father Number One didn't stay long, moving to Texas for a job. He returned for the twins' birth and another time, a few months later, apparently to impregnate Mom once again. They were divorced after that. Mom complained that she’d been pregnant since they met. He moved to El Paso and eventually remarried. I don't remember seeing him until the Nineties when he came to Tulsa to visit his grown sons. Mom's next pregnancy facilitator was an ex-WW II Marine Commando who had served with Carlson's Raiders, he claimed. The only documentation of his service I ever saw was court-martial papers for having sold a Marine Corp. truck to an Australian farmer. He sometimes stalked down the hallway, glassy-eyed drunk, with the blade of his Marine Corp. fighting knife clenched between his teeth and a half-empty fifth of Old Charter in one hand. Although he never acted out his fantasies, by cutting someone's throat, just being in the house with him was terrifying. When I saw him come home with a fifth of Old Charter, I fled to Ron Wheaton’s house, where I knew I was always welcome to sleep in a spare bunk bed. Once I got into an altercation at the Admiral Twin which left me bruised around the eyes. One could say that I lost the fight quite handily. Stepfather Number Two decided it was his duty to teach me about self- defense, so he taught me commando tactics that I could use to kill a person with my bare hands. I thought that was over-kill (so to speak), so I never really practiced. Thankfully, I've not been called upon to use those skills. After I managed to graduate from Will Rogers High School in 1958, I had an opportunity to go to the University of New Mexico, tuition free. I seized it! I had a part-time job which required me to stay in a room above the office of a motel and get up to rent rooms, usually to a man while a woman waited in the car. I could study when I had nothing to do. The job paid room-and-board only. I lasted two years at UNM. Having joined the Air National Guard as a high school junior, I was still a member of the AF Reserve when the Wall was built in Berlin. I was ordered to an activated Air Guard unit in Toledo, Ohio, where I worked in Communications. The Airmen spent eleven months living in a motel near the base, waiting to be ordered to an air base located outside Paris, France. The order never came. I was released. At the time, a TV show named, “Route 66” became popular. My Air Force roommate, Buford Franklin Foster, and I tried to live the theory of the show, which amounted to “travel from town to town, having adventures saving maidens in distress, and working when necessary.” As one might guess, this didn’t work out well. We had some adventures, usually without maidens, actually got jobs (usually for days, not weeks) and traveled from Toledo to Nogales. Back in Albuquerque, “Butch” decided to go to his family home in Willcox, Arizona. At loose ends, I looked up a classmate at UNM who was about to graduate. We had performed together in “cowboy” shows at a tourist attraction in Tijeras Canyon. The job required that we rob the bank, stage duels in the street, and rob the stagecoach halfway through its route through the foothills of the Manzano Mountains. Horses were provided. Little Beaver Town had closed. Bobby suggested I work on his father’s ranch as a cowhand until I found something better. He made a phone call, bought me a tank of gas, and I drove to the top of the Continental Divide between Grants and Gallup. I can’t claim that being a cowhand was much fun, but I got in shape. The work consisted of hard, muscle-straining effort, followed by saddle-time at a furious clip, followed by times with nothing to do. The food was Cowboy Traditional, beef and eggs for breakfast and beef and beans with fried potatoes and a lot of apples from the orchard on the ranch for dinner. Sometimes we slept out at night if we needed to be there in the morning. One older cowhand would always make a circle around his bedroll with his lariat before sleeping. His reason was that a rattlesnake would not cross a lariat. All the cowhands started circling their bedrolls with lassos. One day, on the range, we came upon a rattler who was coiled, hissing, rattling and looking mean as hell! I suggested he throw a loop around the snake and test his theory. He was a good roper. Roping the snake was easy for him. The loop landed on the ground surrounding the snake. That rattler headed for El Paso at an enormous rate of speed, not slowing a bit as he crossed the rope. During off-hours, the hands had a choice of drinkin’ and Rodeoin’. After my first bull non-ride, I decided Rodeoin’ was not all that desirable. Not a single barrel racer was impressed with my performance. I didn’t like drinking much better. The cowgirls where we went, The Forty-Niner Bar in the El Rancho Motel in Gallup, got pretty drunk too. Miss Skilly never taught us how to hold up a dance partner who was having trouble staying on her feet. When Fall rolled around and the foreman culled the cowhands, I volunteered to be one. I took off my cowhand clothes, showered, and put on a suit. In Albuquerque, I hired on as an “Inspector-Trainee” for a company whose business was doing investigations for insurance companies. Most of the “cases” were painfully routine, much like credit reports and dealt with whether a company should sell the “subject” insurance. Inspectors had a quota. Fifteen percent “DECLINE” was laudable and ten percent was required. Each inspector was assigned eighteen to twenty-one cases per day. Well-researched reports were impossible. A fellow I worked with, from West Texas, also an ex-cowhand, was fond of saying about his reports, “I like to think of myself as an author, rather than a liar.” Bon Voyage, Royce Tyler, wherever you are. I did well at the work and found myself in charge of a “sub-office” in Gallup. The only thing I was “in charge of” was myself and an in-box overflowing with cases. I had a heavy caseload. I happened to get a Death Claim in from a major insurer. The deceased had burned to death in her car on a deserted mining road. The insurance company was only interested in knowing if her death was suicide, or not. They had to pay Double Indemnity if it was an accident or murder. I found a lot of evidence of murder, done by a prominent doctor, for whom the victim worked as a nurse. The Sheriff’s investigation called it an accident. The insurance company called off the investigation. My boss decided to keep my report on file but did not share it with the Attorney General. Our company wanted no part of an investigation when politics was involved. The doctor and the politicians who covered for him went free. A job as a Debit Agent for a large insurance company opened. I was hired and sent to an intensive school in Memphis, where I was taught that insurance was a good investment. For a year or so, I sold $5.00 per month life policies until a reference took me to a school for Navajo Children in Ganado, Arizona. The “Prospect” was a just-out-of-college elementary school teacher who qualified to invest (tax free) in a “Tax Sheltered Annuity,” a forerunner of today’s Individual Retirement Annuity. They were a lot of teachers like her at Ganado and the four other school districts on the reservation. She had taken the job because it paid more than public schools in her home state of Mississippi. An apartment was included. She had to travel to Gallup to spend her money. Most of the teachers invested the maximum allowed, $300 per month. I did that gig a couple of years, calling on each of the five school districts one day each week. I moved into a three-bedroom apartment in the El Rancho, sharing it with two other single fellows. One was manager of the hotel, the other sold mutual funds. All three bedrooms had doors that opened onto the swimming pool. One day, I looked out and saw a bikini-clad young lady lying on the deck, reading “Justine” by Lawrence Durrell. Thinking she must be interesting, I put on a bathing suit. “Hi,” I greeted her. Elizabeth Scowcroft Willey (RIP) laid her open book down in a pool of water, and greeted me. She was interesting, a graduate student at the University of Utah, studying Geography. She was undertaking a project of mapping the Hopi Reservation, readily admitting that she may have bitten off the unchewable. Beth and I had dinner that evening and began a friendship. During the winter of 1967-68, I spent as many weekends as I could with Beth at the ski resorts near Salt Lake City. Over a long Fourth of July, we drove to San Francisco and enjoyed the romance of dining on fresh seafood on Fisherman’s Wharf, riding the cable cars and checking out Haight-Ashbury. San Francisco is known as a city for lovers. I understand how it got that reputation. She told me of her adventures on a year-long trip around the world. She and two girlfriends had hitch-hiked through the Arab Countries, which in retrospect, had been a bad idea. All three had escaped with their lives and chastity intact, but there had been some scary situations. I told her of the meager things I’d done and marveled at the difference. We talked about our budding relationship. She told me I was “cute” and good person, but I was boring. She had little interest in stories about other cowboys roping El Paso-bound rattlesnakes. She said I needed to see some of the World and gain experience, which would give me something interesting to talk about. When we arrived in Salt Lake City, she said she didn’t want to see me again. In February of 1969, I bought a one-way ticket to Europe. I didn't go to Europe to escape an un-requitted love affair. There were a number of other reasons. To relate them now would make an already-long story intolerable. I may have reached that limit long before now. |

||||

|

|||||

|

Ron Smith

Posts: 58 View Profile |

RE: The Heritage of A.J. Smith Posted Sunday, September 24, 2017 03:15 PM I''m glad it is not a crime to live on rabbits and squirrels; my dad used to say if it had not been for them and flour gravy, half of Mayes county would have starved to death. If it had not been for hard times, the neighbors would not have had much to talk about. "Grapes of Weath" became kind of an anthem for sections of our colorful "stompin' grounds". Kingston and Harrison Arkansas to Eastern Oklahoma. |

||||

|

|||||

|

Robert Dupree

Posts: 11 View Profile |

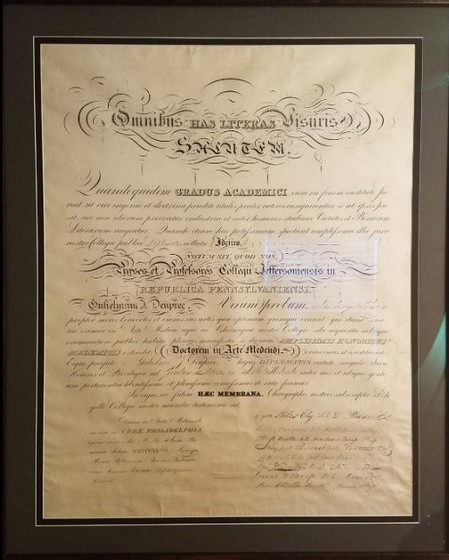

RE: The Heritage of A.J. Smith Posted Monday, September 25, 2017 03:31 PM Very interesting story. I too have Cherokee ancestry. There were two groups of Cherokees involved in the removal. One was the "Old Settlers." The treaties of 1817 and 1819 involved removal of Cherokees to Northwest Arkansas from lands in Alabama and Tennesee. Fort Smith was established in 1817 in order to keep the peace between the Cherokee and Osage who were fighting each other. Will Rogers' Cherokee ancestors were "Old Settlers" as were the ancestors of my paternal grandmother. My paternal grandfather's ancestors were part of the Treaty Party that came to Indian Territory on the Trail of Tears. My second great-grandmother Charlotte Bell and her sister Sarah Caroline Bell were part of the Bell Party led by their father John Bell. Sarah Caroline Bell was married to Stand Watie and Charlotte was married Dr. William J. Deupree of Huguenot ancestry from Mississippi. In General Watie's Cherokee Mounted Rifles were Col. Clement Vann Rogers and Col. William Penn Adair, Will Rogers' namesake and my first cousin 4x removed. Chief Surgeon and brother-in-law to General Watie was Dr. Deupree. Below is a photo of Dr. Deupree's original medical diploma on sheepskin dated 1848 from Thomas Jefferson Medical Academy in Philadelphia.

|

||||

|

|||||

|

A. J. Smith

Posts: 29 View Profile |

RE: The Heritage of A.J. Smith Posted Tuesday, September 26, 2017 08:27 PM What a treasure that sheepskin is, Bob! It's wonderful that you've kept it. I learned some new things from your story and will file it as a part of my "Family History" duties. Thank you for the knowledge. |

||||

|

|||||

|

Robert Dupree

Posts: 11 View Profile |

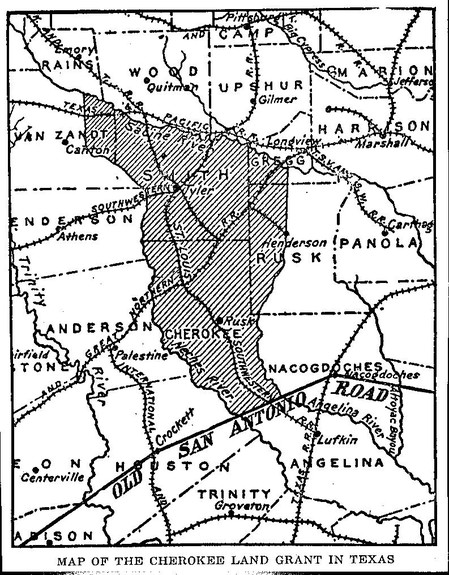

The Heritage of A.J. Smith Posted Wednesday, September 27, 2017 08:28 AM cherokeeLandGrant_1_.jpg I attended a couple of Cherokee functions recently. One was the Fly-In at Will Rogers Birthplace near Oologah. There I met the great-granddaughter of Will as well as our classmate Wayne Bradshaw and his wife Linda. I have some photos from the event on my Facebook page. More recently, I attended a reception at Gilcrease Museum and met the Principle Chief Bill John Baker. He was at a reception for the opening of an exhibition called After the Removal: Rebuilding the Cherokee Nation. I find that much of the Cherokee experience is not covered very well. For example, few people know that Sequoyah, who developed the Cherokee alphabet and has a National Park named for him, died and is buried in Mexico. After the removal on the Trail of Tears, several of the Treaty Party signers were murdered and others, including my ancestors, fled to Texas where the Mexican Government had awarded them a land grant. However, Texas had become a republic and President Mirabeau Lamar drove many of the Cherokees out of Texas into Mexico in 1839 having many of them massacred at the Battle of Neches. My great-grandfather, William Ellington Dupree, was born at Mt. Tabor in Rusk County, Texas. Below is a map of the Cherokee land grant.

|

||||

|

|||||